My Dad Mocked Me at My Wedding — Then 200 SEALs Stood and Saluted: “ADMIRAL ON DECK!”

He said I was a disgrace.

I walked down the aisle in my white uniform — four stars on my shoulder.

My father turned away. But 200 Navy SEALs rose to their feet and shouted, “Admiral on deck!”

This is the story of how I turned betrayal into strength. Of how silence from blood was replaced by the salute of brothers. Of how a woman in uniform rewrote the rules of respect, legacy, and forgiveness.

If you’ve ever been underestimated by family… If you’ve ever risen above what was meant to break you…

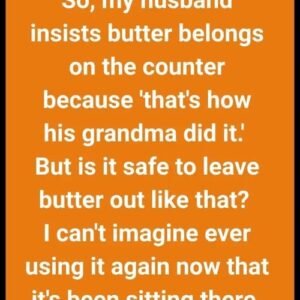

You’re wearing a uniform to your wedding. Disgraceful. That was the message. Five words from a number I hadn’t saved in years. But I knew who it was. My father, retired Colonel Frank Holstead, former 82nd Airborne, full bird and forever disappointed in his only child.

The text lit up my phone just as I stood behind the closed chapel doors, heart steady beneath my white Navy dress uniform. The gold buttons gleamed. Four stars on my shoulder. Rows of ribbons I’d earned, not collected, decorated my chest like silent sentinels of the past 25 years. Behind me, my team stood at parade rest. Some wore medals I’d pinned to their uniforms myself. Others carried scars we never spoke about, the kind that didn’t always bleed. And in front of me, just beyond those doors, 200 SEALs waited. So did the man I was about to marry.

The text burned in my palm. I should have deleted it. Instead, I stared at it for a full minute, not in shock, but clarity. This is who he is, and this is who I’ve become.

The doors opened. As I stepped forward, heels sharp against polished wood, the SEALs — every last one of them — rose to their feet in perfect sync, and someone shouted, “Admiral on deck.” The chapel echoed with the sound of 200 decorated warriors snapping to attention, uniformed, upright, unshaken. My throat tightened — not from sadness, from honor. My father wasn’t here, but my family was.

You probably want to know what led to that moment — to me walking down the aisle, not in white lace, but in a uniform soaked with history, memory, and sacrifice. So, let me take you back.

I was born into the military, not by enlistment but by blood. My father believed in duty above everything. Discipline, honor, obedience. Those were his commandments. And in his eyes, only sons were supposed to carry that flag forward. When I was ten, he took me to an Army–Navy game at the stadium — not to enjoy it, to show me what I’d never be. He said it while standing next to me: “You’ll never wear those colors, kid. Leave the uniform to men who can handle it.” I didn’t cry. I never did. Instead, I listened, watched, remembered.

My room was decorated with metals he never let me touch. I ironed his dress uniforms growing up, memorized every regulation before I was sixteen. But the moment I told him I’d applied to Annapolis, he didn’t speak to me for a year. The silence was louder than anything he could have said. When I was accepted, he dropped a manila folder on my bed — inside, applications to law schools, nursing programs, teaching positions. Not a single one with an anchor on the seal.

At the Naval Academy, I learned fast that being a woman in uniform meant walking a razor’s edge twice as sharp, half as fair. I worked harder, studied longer, endured more. But I earned every bar. I rose through the ranks one steel moment at a time. And each time I was promoted, I called him. He never answered. Eventually, I stopped dialing, but the silence still spoke.

Fast forward to the morning of my wedding. I wasn’t nervous. I’d stood on foreign soil with mortars falling around me. This — this was just a ceremony. But the uniform, the one I wore that day, wasn’t a statement. It was a truth. My fiancée James was a civilian — quiet, intelligent, grounded. He once told me, “You in uniform is the most honest thing I’ve ever seen. Why would I want you in anything else?” So, I wore white — just not his version of it.

The plan was simple: a modest ceremony at the naval chapel. No bridesmaids, no frrills, just us and the team. The SEALs I’d led, fought beside, and bled for. They showed up uninvited. Said it was non‑negotiable. Said they couldn’t let me walk alone. I didn’t expect a crowd. I didn’t expect tears. And I didn’t expect that text. Disgraceful. He didn’t say congratulations. He didn’t say good luck. He said disgraceful. That was his gift to me.

So I gave him mine. I walked down that aisle in a white uniform, four stars on my shoulder, to the sound of 200 men saluting not my title but my life. That was the moment I knew blood didn’t salute — but honor did.

I grew up in a house where the American flag flew higher than feelings and where “I love you” was always implied but never said out loud. My father wasn’t abusive. He was precise. Every inch of our lives was arranged like a parade formation: meals at 1,800 sharp, shoes lined at 45‑degree angles, silence during 60 Minutes every Sunday night. When I scraped my knee as a kid, he’d toss me an antiseptic wipe and say, “Soldiers don’t whine.” Even back then, I didn’t mind. I admired him, respected him, wanted to be like him. That was my first mistake.

Colonel Frank Holstead served three tours in Vietnam and never stopped reminding people of it. To his credit, he earned everything the hard way — climbed from enlisted to officer, led men through jungles and ambushes. Bronze Star, Purple Heart. He kept the medals in a glass case in his study next to a black‑and‑white photo of him in dress greens, back straight, jaw tight. He called it the altar. I wasn’t allowed to touch it, and I didn’t — until he made it clear I’d never be worthy of it.

My mother, on the other hand, was soft where he was stone. She taught literature at the local high school, wore flowy cardigans, and read me Emily Dickinson at bedtime. She called me her Stormbird — Wild, Fierce, a little too strong for my own good. She was the only reason I didn’t leave home the day I turned eighteen.

I remember sitting between them at dinner once in high school. I’d gotten an award for a leadership program, and I told him I wanted to go to a summer boot camp in Annapolis. Mom beamed. My father didn’t look up from his peas. “You’re not cut out for the military. That’s not how we build families.” He said it like I was applying to join the circus.

When I received my acceptance letter to the U.S. Naval Academy, I was eighteen and shaking with joy. I brought it into the living room, held it out like a peace offering. Dad stared at it for a full thirty seconds, then said, “So, you’re serious about this nonsense.” I told him I was. He didn’t speak to me for two months after that. Not a word. He canceled our standing Saturday breakfasts, skipped my graduation party. It was the first of many silences that would build a wall between us.

But Mom never stopped trying. She called me every Sunday during my first year at Annapolis, sent care packages full of tea, granola bars, and annotated poetry. Once during my pleb summer, I broke down on the phone with her after a drill instructor had screamed in my face for a solid hour. She didn’t cry. She just said, “Storms aren’t meant to stay grounded. Let the wind harden you, not break you.” She passed away three years later. Breast cancer — fast. Cruel. Dad didn’t even tell me she was in hospice until the final week. When I arrived, her hair was gone, her skin paper‑thin. He stood in the corner of the hospital room, arms crossed, saying nothing. She reached for my hand and whispered, “Keep flying.” She was gone before sunrise.

After her funeral, I returned to base. I expected a call, a letter, anything. Instead, I got an email from my father — three sentences: The funeral was nice. I hope the Navy is treating you well. I still don’t understand your decision. That was it.

Over the years, every milestone in my career became a fork in the road, and he always turned the other way. When I pinned on Lieutenant Commander, I mailed him a photo. He didn’t respond. When I received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, I sent a copy of the ceremony link. Still nothing. At one point, I wondered if I should just give up, stop reaching out. But something in me kept hoping he’d show up.

When I was promoted to Rear Admiral, the youngest woman in my command to reach that rank, I tried one last time. Sent him a handwritten note — short, direct: I know you don’t agree with my path, but I took your lessons, all of them, and I’ve led men and women with the same values you taught me. I’ve done it in uniform. I’ve done it well. I never got a reply, but I did hear through a mutual friend, one of his old Army buddies, that he read the letter three times and tore it in half.

So when I received that text on my wedding day — you’re wearing a uniform, disgraceful — it wasn’t a surprise. It was a final confirmation. He never saw me as a soldier. He never saw me as a daughter — only as a defector. But here’s the thing about legacy: it doesn’t flow automatically through blood. It has to be earned. And somewhere along the way, I stopped chasing his approval. I built my own altar. And I filled it with the lives I’d led. Protected. Trained. And sometimes buried. That’s what I carried with me down that aisle. Not shame. Not resentment. Just truth.

There’s a saying in the Navy: Smooth seas don’t make skilled sailors. By that logic, I must have become a damn admiral in the perfect storm. I never set out to break records. I just didn’t want to break — not under pressure, not under fire, and especially not under judgment.

After graduating from Annapolis, I was stationed in Okinawa. My first assignment wasn’t glamorous — paperwork, logistics, keeping men twice my size in line. Most figured I wouldn’t last a year. I lasted five. I wasn’t the loudest voice in the room, but I paid attention. While others chased promotions, I chased excellence. Every time a door slammed shut, I learned the hinges. Every time I was underestimated, I took notes.

There was a turning point — 2007, a classified operation off the Somali coast. One of our supply teams was ambushed during a recon run. Two were injured, one trapped. I was a lieutenant commander at the time — technically not required to deploy boots on ground — but I went anyway. The situation turned fast. We were pinned behind rusted shipping containers, bullets chewing through steel like paper. One of our boys was bleeding out, his leg mangled below the knee. I dragged him forty yards under fire, cinched a tourniquet with one hand and radioed medevac while my other hand held pressure on his femoral artery. By the time we reached the evac chopper, my uniform was soaked red and I’d taken two pieces of shrapnel through my side. I refused the stretcher. They called me Iceback after that. Said I bled ice, not blood. But I wasn’t proud of the name. I was proud the kid lived. He still sends me a Christmas card every year. His daughter’s name is Avery — after me.

That was the moment command started to take notice. Suddenly, I was the exception. They said I had grit, leadership, po under pressure. But what they didn’t see were the hours I spent in recovery, grinding my mers through pain, teaching myself to walk without a limp. Pain never stopped me, but invisibility did. Even when I saved lives, someone else always got the headline. That’s how it is when you don’t fit the mold. But I learned to stop chasing spotlights. Instead, I became the lighthouse.

By 2015, I was commanding training operations at Coronado. SEAL selection had its own politics, some of it ugly. I watched good candidates get washed out for the wrong reasons. So I rewrote the training modules — quietly, thoroughly — implemented new safety protocols, mental‑resilience checkpoints, and recovery systems. Within a year, dropout rates dropped by 12%. Injury rates hald. I didn’t get a medal for it, but I got something better: respect. Even the old brass started calling me ma’am with sincerity. And the men — the ones who mattered — they followed me without hesitation.

When I made Rear Admiral, I received a standing ovation from my unit. The next morning, I checked my inbox. No email from my father. Not that I expected one. But later that week, I ran into one of his old West Point buddies at an event in D.C. He approached me, glass of bourbon in hand, and said, “Frank says the Navy is getting soft if they’re promoting women like you.” Then he smiled. “But he keeps your picture in his office. Won’t admit it, though.” That stung more than I wanted to admit. Love in silence still felt like absence.

I kept rising. It didn’t feel like a climb — more like a long uphill swim through cold, invisible currents. I served in South Korea, Bahrain, and eventually Norfolk. Everywhere I went, I left things better than I found them. People started calling me a quiet reformer. I preferred just officer.

There was a moment, though — the one I can never shake. It was after a suicide on base. One of our brightest instructors. Quiet guy. Never missed a mark. No signs, no flags, just gone. I was the first to read his file. Tucked inside was a note: Tell Admiral Holstead thank you. She’s the only one who ever saw me. I didn’t cry at first, but later that night, alone in my office, I pulled off my ribbons one by one and wept. Not from weakness — from the weight. After that, I made it policy every unit under my command would have mandatory monthly check‑ins, no excuses. You didn’t just train hard. You trained with eyes open to the people around you. It didn’t make headlines, but it saved lives. That, to me, was real leadership.

When the final promotion came — to full admiral — I was standing alone on the deck watching sunrise over the water. The message arrived from Navy Personnel Command: four stars. No parade, no family, just the sky and silence. And that felt right — until a few days later, a letter arrived in my mailbox. No return address, handwritten. They’re just making you a symbol. Five words. My father’s handwriting. It was the only thing he’d written to me in fifteen years. Even in my highest moment, he couldn’t help but try to reduce it, to shrink what he couldn’t control. I burned the letter in the sink. Then I ironed my dress whites because I’d need them soon for a ceremony — my wedding.

James wasn’t military. He wasn’t the type to shout orders or polish shoes until they reflected the soul. He didn’t carry scars the way my team did, but he understood structure. And, more importantly, he understood me. We met during a Department of Defense working group. He was a civilian intelligence analyst assigned to a cyber security task force I was overseeing. We collided over protocol during a briefing. He thought my reporting format was inefficient. I told him efficiency isn’t always found in the fastest route. Sometimes it’s found in clarity. He smiled, then revised his entire presentation overnight using my format. Said, “You were right.” That was the beginning.

James never once flinched when I got called away at 2 a.m. Never questioned why I couldn’t talk about certain missions. Never made me feel like I had to downplay what I’d earned. Instead, he asked me things like, “How do you teach calm under chaos? How did it feel the first time someone called you admiral?” He once told me, “Most people love parts of you. I love all of you — the steel and the softness, even the parts you try to carry alone.” When he proposed, it wasn’t with flash — no skywriters, no crowds — just the two of us on a pier at sunset, boots dangling over the edge. He opened a small, simple box and said, “Let me serve beside you, wherever that means.” I didn’t cry. I just said yes.

Planning the wedding was delicate. James didn’t want a spectacle. Neither did I. But our friends — my team especially — insisted on something more meaningful than vows whispered in a courthouse. We decided on the naval chapel: simple, formal, respectful. I didn’t want a ball gown. He didn’t want a tux. He wore a clean navy‑blue suit. I wore my white full‑dress uniform. It wasn’t a political statement. It was personal — the only thing I’ve ever worn that felt like truth.

A week before the wedding, I sent my father a card — not out of hope, just out of completeness. Inside, I wrote, “I’m getting married this Saturday. 1300 hours at the naval chapel. You’re welcome to attend. I’ll be in uniform.” That was it. No RSVP ever came.

The night before the wedding, James and I agreed to sleep separately — a tradition. He stayed with a close friend. I stayed on base in the guest quarters, quietly reviewing my ceremony notes. At midnight, I ironed my uniform — slow, careful, reverent. As I passed the brass over the shoulder epaulettes, my eyes welled. Four stars. I’d worn them in combat, in strategy briefings, in moments of grief and command. But tomorrow I’d wear them for love.

The morning arrived clear and bright — that sharp navy‑blue sky you only get on the East Coast in spring. The SEALs showed up in formation outside the chapel. Some I hadn’t seen in years — men I trained, deployed with, pulled out of wreckage, delivered eulogies for their friends. No one told them to come. They just did.

Fifteen minutes before the ceremony, I stood behind the chapel doors, flanked by two of my oldest team members, both retired, both now fathers, with gray in their beards. One leaned in and said, “You walked us through hell. Let us walk you to something better.” I was ready, peaceful — until the phone buzzed. I glanced down. A message from a number I hadn’t saved but would never forget: You’re wearing a uniform to your wedding — disgraceful. No name, no congratulations, no apology for the silence of two decades. Just that.

I should have felt anger. Instead, I felt something colder: clarity. This was his final attempt to shame me back into the box I’d long outgrown. But shame requires agreement — and I no longer did. I tucked the phone into my pocket, smoothed my cuffs, took a deep breath, and when the chapel doors opened, every man in that room stood — not because they were told to, but because they chose to. A single voice rang out: “Admiral on deck.” The echo bounced off stained glass and polished wood. My heart didn’t race. It settled. Because in that moment, surrounded by people who’d seen me at my fiercest, my most broken, my most human, I knew I wasn’t walking toward tradition. I was walking into a truth I had forged from fire.

I walked that aisle with steel in my spine. Not because I was trying to prove a point, but because I didn’t have to. I had already become the point.

The aisle felt longer than I expected. Not in the daunting, anxiety‑inducing way most brides describe, but in the quiet, reverent sense of crossing a line from one life into another. My boots struck the floor in rhythm, crisp and even. And I didn’t walk alone.

To my left, Chief Petty Officer Marcus Hill — a man who once pulled me from a downed helicopter in Kandahar. To my right, Senior Chief Torres, who’d lost a leg in Syria and still beat everyone in early morning PT runs. They were supposed to be guests. They insisted on being escorts.

I saw James standing near the altar. He wasn’t crying, but his eyes shimmered, and his hands were folded neatly behind his back, standing at ease, the way he knew I preferred. Behind him stood our officiant — a Navy chaplain I’d served with overseas. He wore his ribbons, too. We all did. No masks, no pretense — just the truth worn on our chests.

As I approached, I caught sight of the pews — rows and rows of service members, most in full dress, every seat filled. And as I stepped into the clearing before the altar, the room fell into perfect silence. Then: “Admiral on deck.” Voices rang in unison. Every soldier, sailor, SEAL, and officer rose in one swift motion — not for protocol, but for respect. My breath caught. Not because I needed validation, but because I hadn’t realized until that very moment how long I’d gone without being seen fully, without hesitation, without caveat. These were warriors — men and women who’d faced death with me, who had trained under my command, who’d heard my voice in the heat of gunfire and followed it because they trusted it. They weren’t just saluting a rank. They were saluting a life.

I reached James and gave a small nod to Hill and Torres. They stepped back with silent dignity. The chaplain opened his binder, but waited. There was something sacred about the stillness. Then James stepped forward, took my hands — gloved, firm — and whispered, “I don’t need to say vows to know I’m already married to your courage.” That’s when I felt it. Not pride — belonging.

Our vows were simple. We promised to serve each other — to protect not just each other’s bodies, but each other’s peace. To honor not just joy, but sacrifice. I didn’t say for richer or poorer. I said, When orders come, we follow together. When they don’t, we find purpose on our own terms. James vowed to build a life with me that didn’t ask me to dim, to carry the weight with me, to never ask me to be less. When the chaplain pronounced us husband and wife, the room didn’t erupt. It stood still — quiet with reverence. Then came the applause — thunderous, earned, honest, the kind that fills the lungs, not the ears.

We walked out under an arch of crossed sabers, blades gleaming in the spring light. A tradition usually reserved for officers. This time it was the enlisted who held the blades aloft. It meant more that way. They were the ones who truly knew.

Later at the reception — a modest affair on base — one of my former SEALs approached me. Big guy, tattooed forearms, rarely spoke more than a few words at a time. He looked down at my boots, then said, “We never stood for you because of your rank, ma’am. We stood because you never made us feel small.” Then he hugged me tight like a brother. I wasn’t used to being embraced like that, not outside the battlefield, but I let myself accept it. Not because I needed comfort — because I had earned it.

Around midnight, the crowd thinned. The cake had been cut. The toasts were over. I stepped outside to catch some air. The moon hung low over the waterline. James found me there, arms folded, watching the waves.

He asked gently, “Did you hear from him?”

I nodded. He waited. Then I said, “He called it disgraceful.”

James didn’t react right away. Just stood beside me for a moment. Then he asked, “Do you believe that?”

I looked down at my uniform — the gold trim, the ribbons, the stars. I thought about the SEALs rising to their feet, about the respect in their eyes, the quiet dignity of their salute. I looked back at James. “No,” I said. “I don’t.”

There are moments that define a life. Some come with medals, some with silence, some with a single text. But others — they come with a room full of warriors who don’t have to stand, but do.

It happened three days into our honeymoon. We were in Maine. James had found a quiet coastal inn, the kind with creaky floors and the smell of sea salt soaked into the walls. No press, no pomp — just us; foggy mornings and blueberry pancakes made by someone’s retired uncle named Roy. I hadn’t looked at my phone since the ceremony. But that morning, James gently handed it to me. “You should see this.”

There was a message, not from my father — from my cousin Clare. A single photo, no caption. It was the parking lot of the chapel taken from across the street. In the corner, unmistakable in his rigid posture, stood Colonel Frank Holstead — full dress uniform, arms crossed, back straight, watching, not entering. And then another photo, a moment later — the one that caught him mid‑turn. Leaving.

I stared at it longer than I expected. I didn’t know what I was looking for. Regret, softness, closure. All I saw was a man who chose distance over redemption.

James stood behind me, quiet, then said, “He came, but he still couldn’t stand.” That was when I knew: the moment 200 SEALs had saluted me, he had turned his back.

Later that week, I received an invitation from the Pentagon. They were hosting a closed‑d dooror event, leadership and transformation roundt on the future of command. The brass wanted me to give a keynote on ethics in modern leadership. Not because I was the first woman admiral, but because I’d implemented systems that had actually saved lives. I almost said no. Then I remembered the young sailor who’d written me that suicide note: She’s the only one who ever saw me. So I said yes.

The night of the speech, I stood in full uniform under blinding lights in a room filled with ribbons and rank, politicians and power. I told stories of courage — not mine, theirs — the warriors who followed orders into fire, not because they were told to, but because they trusted the one giving them. I talked about reform not as a threat, but a responsibility. I told the room, “Authority isn’t about being the loudest voice. It’s about being the calmst in the chaos.” And then I closed with this: Respect isn’t inherited. It isn’t given by blood. It’s earned by showing up, standing up, and doing right even when no one’s watching.

There was silence, then a standing ovation. The next morning, a letter arrived at my office. Handwritten, no return address, but I knew the script immediately: I didn’t enter the chapel because I didn’t know how to sit among people who saw in you what I refused to. I didn’t salute, not because you didn’t earn it, but because I no longer knew how to honor what I didn’t understand. I was wrong. If you’ll let me, I’d like to talk. No uniform, no protocol, just a father trying to understand a daughter he never took the time to know. — Frank.

I read it three times. Didn’t cry, didn’t burn it, just sat with it. James came home that evening and found me at the kitchen table. He raised an eyebrow. “He finally said something.” I nodded, handed him the letter. When he finished, he asked, “Do you want to meet him?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t owe him anything.”

“No,” he said gently. “But maybe you owe yourself the choice.”

The next week, I met him at Arlington. We stood at my mother’s headstone, the grass trimmed, the silence absolute. He wore civilian clothes — slacks, jacket — no pins, no bars, no armor. Just a man, older, smaller than I remembered. I arrived in uniform not to make a point, but because it was who I was. He didn’t hug me, didn’t try — just said, “You look like your mother when you stand like that.”

We talked — not about the war, not about medals — about grief, regret, how silence can feel like strength but really just hides fear. Before we parted, he stepped back, straightened, and in a slow, deliberate motion, he saluted. Not a crisp military gesture, not perfect form — but earnest. And it landed harder than any medal I’d ever received. I returned the salute — not because he’d earned forgiveness, but because finally he’d chosen truth.

That night, I lay beside James and whispered, “He saluted.” James didn’t ask what it meant. He just held my hand, and we fell asleep to the sound of rain on the roof.

Some people think revenge is about destruction, but sometimes the most powerful reckoning is recognition.

Six months after the wedding, I received a call from Navy Personnel Command. They asked if I’d consider taking oversight of a new joint operations initiative — one designed to restructure inter‑branch training protocols and integrate ethical command leadership. It was the kind of project I would have dreamed of twenty years ago. Now, it felt like legacy in motion. I accepted.

And as part of the project, I returned to bases I hadn’t stepped foot on in years — including the one where I’d first led a platoon of skeptical, stubborn sailors who thought I was just a publicity stunt. They remembered me, and they stood when I walked in.

On one of those visits, I ran into a familiar name on the roster: Corporal Avery Patterson. I smiled. The little girl named after me — now in boots of her own. She told me she joined because her dad said I saved his life. Sometimes you don’t realize how far your reach extends until it circles back and salutes you.

Back at headquarters, I was approached about a civilian partnership with the Defense Education Initiative. They wanted to use my leadership methods to help train ROC instructors across the country. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was meaningful. When they asked me what to call the program, I said, “Call it the Salute Standard. Not for what’s worn, but for what’s earned.”

Then came the final letter. It arrived in late spring — cream envelope, heavy card stock, my name handwritten in block letters from my father. Inside: I watched your speech. I’ve read your proposals. You built a career that wasn’t about proving anyone wrong, including me. You built it to save lives. And I finally see that now. I miss the standing ovation, but I hope I haven’t missed my chance to stand beside you, even in a small way. — Dad.

He included a single photo from my wedding taken from a distance behind the last row of pews. I hadn’t known someone had captured it. In the image, 200 men stand saluting. And in the back, a lone man — arms at his sides — watching. Not saluting. Not yet.

Weeks later, I invited him to attend the ROC keynote address. He came, sat in the back, said nothing. But afterward, as I stood outside shaking hands with cadets and instructors, he walked over, took off his cap, extended his hand. I took it. No cameras, no audience. Just the two of us.

“I’m proud of you,” he said. Then quieter: “And I’m sorry it took me so long.”

I nodded — not because it fixed everything, but because it started something.

That night, James asked me, “Are you happy with how it turned out?” I thought about it for a long time. Then said, “I’m satisfied. Not because they suffered, but because real change happened. The buildings are safer, the program stronger, the silence broken.” And the girl who once ironed her father’s uniform now has cadets ironing theirs because of what she built.

He smiled and kissed the top of my head. “Would you ever forgive him?” he asked.

I said, “Forgiveness isn’t a transaction. It’s a path.” And today, we took a step.

One year to the day after my wedding, I stood on a stage accepting the Department of Defense’s Excellence in Ethical Command Award. James was in the front row. So was my father. As I stepped to the podium, a group of cadets in white stood and saluted. And from the far right corner, so did Frank Holstead — this time with his hand to his brow.

Afterward, as we walked out into the warm evening air, my phone buzzed. A message from one of the SEALs from my unit: Still thinking about your wedding day, ma’am. Never seen that many warriors cry during a ceremony. That was the day we realized something. Blood didn’t salute, but we did.

I looked at James, showed him the message. He nodded.

“You going to respond?”

I typed back: Some gifts can’t be returned, but some salutes — they stay with you forever.

Some people say revenge is about crushing what crushed you. But I’ve learned that the most lasting power is choosing to build what they never believed you could. You don’t always have to swing back. Sometimes you just have to stand tall. Let them look up to reach you.

If this story moved you, take a moment to reflect. Who stood for you when others didn’t? When did you rise above what was meant to break you? Leave a comment if you’ve ever turned betrayal into clarity and silence into your own kind of salute. And if you’d like to hear more stories of resilience, truth, and quiet triumph, please subscribe. We rise together.

I didn’t hear the applause after the award so much as feel it—like surf you stand inside, the rhythm bigger than anything your lungs could plan for. When it was over, when the lights cooled from white to human, James and I slipped out a side door into a corridor that smelled like mop water and new carpet. He squeezed my hand once, and we walked without speaking, two shadows in dress blues and a navy suit.

Outside, Washington exhaled. Summer had turned the air soft; the Potomac dragged the moon along its back. A staff sergeant opened the sedan’s door and nodded, not to my rank or my ribbon rack, but to the long field of work between us. The door closed. City lights stitched themselves into a single voltage line heading home.

Home, for us, was a row house in a neighborhood that had been beautiful before anyone noticed and stubborn after. The porch light was out—James had the habit of unscrewing it to stare at stars that never showed up in a city with opinions about light. Inside, the house held its breath. When I dropped my cover on the entry table, I felt the relief you never get from medals: the click of a key becoming still.

“Tea?” he asked.

“Water,” I said, and he poured it into a glass heavy enough to stay where it landed.

We sat at the kitchen table, the one that wobbled unless you pressed a thumb against the back left leg. He did, without thinking. I traced the grain line with a nail and let the night empty out the names from my head—Kandahar, Coronado, Norfolk—like a field stripping until readiness is the only thing left.

“He saluted,” I said finally.

James nodded. “And you returned it.”

“It landed,” I said, and the word sounded like a plane that had earned its runway.

People assume awards end a story. They don’t. They begin the chapter where you have to live up to the speech.

The Joint Ops initiative that called me the week after the wedding unfurled into a map the size of a wall: red pins where we’d had preventable injuries, blue pins where we’d piloted training reforms, gold pins where we’d built something that outlasted the leadership who ordered it. In the middle of the map was a note written in my handwriting, copied onto the whiteboard by a captain with square shoulders and a round kindness: WE TRAIN PEOPLE, NOT MYTHS.

Old myths don’t go easy. They put on dress blues, clear their throats, and quote Patton at you between sips of coffee that tastes like 1973. The first time I briefed the inter-branch council on reshaping selection to reduce non-fatal heat casualties and increase post-injury return rates, a Marine two-star with a jaw like a cinder block leaned back in his chair and said, “Admiral, we don’t need to make it comfortable. We need to make it worthy.”

“Worthy,” I said, “is when a mother pins a trident on a chest that still has a heartbeat ten years later. Worthy is a standard you can measure the same way at 0400 on hell’s own beach and at a VA clinic in February.”

He didn’t smile. He didn’t argue either. You learn to take the silences that aren’t surrender and call them soil.

We piloted at Coronado first because that’s where I could read the currents blindfolded. We added micro-recovery intervals in the second half of the day, not to soften anything, but to keep men from tipping into heat stroke they couldn’t climb back out of. We instituted a peer-check protocol that a SEAL master chief named Sloan wrote on the back of a chow hall napkin: LOOK ‘EM IN THE EYES. IF THEY’RE NOT HOME, BRING ‘EM BACK.

The first month, the injury report came in thinner. The third month, it wasn’t a fluke. Dropout rates didn’t fall from the standard; they fell from the margin where the body quits before the mind does. The old guard called it coddling. The new guard called it math. Nobody called it easy.

At the end of Quarter Two, I flew to San Diego to stand on asphalt older than most of the men grinding it into memory. The bay hunched blue and rehearsed. A class jogged past, sand a second skin. Sloan sidled up beside me, his gait as familiar as my own. “You see the kid on the end?” he asked.

“Hat brim too straight,” I said.

He smiled. “Good eye. Comes from a family that irons their socks. Faints if he misses breakfast. He learned how not to faint.”

“That a new evolution?”

“It is now.”

We watched them disappear into a wall of heat haze that made California look like a mirage pretending to be a state. He cleared his throat. “I heard what they said at the Pentagon.”

“They said many things,” I said.

“The one about symbols.”

I didn’t answer. He knows my silence taxonomy. He let it sit until it became truth instead of bait.

“You know why we stood in that chapel,” he said finally. “It wasn’t because of the stars. It was because in 2007 you were bleeding through your blouse and still counting heads.”

“I was counting names,” I said.

“Same thing when you do it right,” he said.

Frank wrote letters like a man building a bridge out of planks that might not hold. Short. Measured. No ceremony. He wrote about the veterans’ breakfast he started attending, where the waitress calls everyone “sir” whether they rate it or not and sets a pitcher of coffee down like a promise. He wrote about a boy at the end of his block who salutes on trash day and gets it wrong, every time, because his hand wants to become a wave.

He wrote about the altar in his study. How he moved the medals into a lower case so the neighbor’s kid could see them when he stopped by to ask if Frank could fix his bike. “He called me Mister Holstead,” he wrote. “Then he called me sir. I told him to call me Frank. He asked me if I knew any admirals. I told him no. Then I told him yes.”

The third letter included a book—Emily Dickinson, the Collected. My mother’s handwriting bloomed in the margins like wildflowers nobody could keep inside a fence. On page 214, under a poem about storms, a note in her hand: FOR STORMBIRD. WIND IS MERELY A PLACE TO LEARN.

I took the book to Arlington the next Saturday. We met by the headstone with her name carved into white. He was there first, as if time were a uniform he still wore.

“I brought her voice,” I said, holding up the book.

He swallowed, then nodded. “Read to me,” he said, and for the first time in my life my father asked me to tell him something he didn’t already know.

When I finished, he didn’t say thank you. He said, “I thought I was protecting you by keeping you out of a fight I thought only men could survive.” He looked smaller in the shadow than in the sun. “Turns out you were protecting people I couldn’t reach by walking into it.”

“We can stop keeping score,” I said.

He nodded. The salute didn’t come this time. He didn’t need a gesture. He needed practice.

It was the kind of emergency that refuses to call itself that. A cyclone idled off the Carolinas and thought about being worse. A frigate thought about a course correction and made it too late. By the time the watch officer called my cell, thunderheads had braided themselves into a fist.

The coordination center snapped to like a spine. Screens lit—radar, satellite, three lines of numbers only six people in the room could read. I spoke in verbs. Move. Hold. Raise. Drop. A junior analyst with a haircut that still remembered youth soccer missed a decimal and corrected it before the decimal knew it had been wrong. James stood in the back, not because he needed to be there, but because sometimes love is proximity you don’t have to explain.

“Ma’am,” the comms chief said, “we’re losing the stern cam.”

“Then make the bow tell us the truth,” I said. “And get me the helmsman.”

A voice came through the squawk tinny and steady. “Helm.”

“This is Admiral Holstead,” I said, and the word admiral turned into a rope because right then the ship needed something to hold. “You’ve got twenty degrees of error that’s about to become thirty if you respect that storm. Don’t. Lean into it. Now.”

He leaned. You could hear it—a ship correcting itself like a man deciding he will not fall this time. The cyclone slid its shoulder past us, irritated, then went to go be dramatic where nobody important was.

When the room exhaled, someone clapped. It wasn’t for me. It was for the fact that the sea had let us negotiate tonight.

James met me at the door when we left. He tucked my hand into his elbow like we were on a promenade in a city with better manners than weather. “What are you thinking?” he asked.

“That ships respond better to blunt truth than fathers,” I said, and he laughed the way he does when the joke is a little bit mercy.

The Salute Standard took root in places I never expected—coast guard stations with budgets that realigned between Tuesday and Wednesday, police academies that asked outdated questions in shiny classrooms, university ROTC programs where cadets had learned too early to hide their competence behind jokes. We sent mentors instead of manuals. We sent people like Sloan, like Torres, like a lieutenant named Han who could make a room stop posturing by putting a hand on a table and saying, “Tell me where you got hurt. I’ll tell you how to train around it.”

The first public pushback came from a columnist who prefers provocation to research. He published a piece with a headline that used my name like a dare and my rank like an epithet. The gist: We were turning warriors into patients.

Torres texted me the link with three words: DO WE CARE?

I wrote back: WE COUNT.

We counted the trainees who finished BUD/S and walked into a decade where they could carry their kids on their shoulders. We counted the spouses who didn’t have to pick up pieces because we taught their people how not to shatter. We counted the funerals we didn’t have, which is a number nobody likes to publish because it’s an absence and absences don’t sell ads.

A month later, the same columnist emailed me privately to ask if he could sit in on a session and write an “update.” I told him no. I invited him instead to stand on the beach at 0300, no cameras, and watch a class go into the surf zone and come out shoulders squared, not because the water told them who they were, but because the man beside them did. He didn’t take me up on it. I didn’t publish that either.

On our first anniversary, James made pancakes in a cast-iron skillet that has lived longer lives than both of us combined. He plated them in stacks that looked like architecture. We ate on the back steps with our feet bare, and the city pretended to be a small town just long enough for us to believe it. After breakfast, we walked to the park that smells like hydrangeas and ozone. He stopped under an oak that has seen more oaths than a courthouse and pulled a piece of paper from his pocket.

“I wrote vows I didn’t get to say,” he said.

“You said everything,” I said.

“Then this is for me,” he said, and he read them—lines about choosing the ordinary because we’d both had a lifetime of extraordinary, about making a practice out of quiet, about building a house that doesn’t need a porch light to find its way home.

“Your turn,” he said.

I don’t write vows. I issue orders that sound like poems once you give them enough time. “We will sit down when there is no time to,” I said. “We will tell the truth before it’s pretty. We will stand down when standing up would be easier. We will keep a table with a wobbly leg and fix it together, every day.”

He saluted me then, ridiculous and perfect. I returned it, crisp as gospel.

Frank asked to meet James. He asked like a man approaching a checkpoint without his papers, hopeful but braced for a turn-back. We chose a diner where the coffee is loyal and the fries understand their job. When we walked in, he stood. When he shook James’s hand, his grip was firm enough to be a kindness, not a contest.

“I watched you on C-SPAN,” he told James, and James blinked because C-SPAN is to romance what rations are to cuisine. “You looked like a man who knows how to listen.”

“I try,” James said.

Frank nodded. He didn’t say I’m proud. He didn’t need to. He had learned that pride is a feeling you show with your presence, not your adjectives.

He told us stories from the eighties nobody puts in movies—bad food, good sergeants, radios that only worked when you cursed in the right key. He listened to mine from the twenty-teens—good food, better sergeants, radios that worked until they didn’t because batteries pretend to love you and then ghost you.

The waitress called him sir twice. The second time he said, “Ma’am, Frank is sufficient.” She looked at me and said, “He’s trying.” I said, “So am I,” and we were all right.

When we left, he walked us to the door. On the sidewalk, he straightened his jacket and said, “I would like to attend one of your trainings.”

“Command course?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “The one where they teach you how to see people before you break them.”

“We can all stand a refresher,” I said.

The hearing was inevitable. Anything that threatens a budget line or a myth finds itself at a long table under longer lights. I wore my uniform because we were discussing the body, and I wanted mine to testify. The subcommittee chair introduced me with a biography that felt like he’d read a dossier on a stranger. When he finished, he blinked kindly and asked, “Admiral, are you lowering the standard?”

“No,” I said. “I’m making sure we don’t mistake negligence for tradition.”

A congressman with a gleam like polished brass leaned forward. “But the attrition rate—”

“—is a blunt instrument,” I said. “It doesn’t tell you who you lost. It tells you how many. We are measuring how many we keep without killing.”

Murmurs. Phones slid under tables. Someone tweeted a half-truth because whole truths don’t fit inside character counts.

Then a woman at the end of the dais, a veteran with a smile that had stopped wars at family dinners, said, “Admiral, if this were your son or daughter, would you want them to go through the old selection or the new?”

“I don’t have children,” I said. “But I have five thousand people whose names I can tell you without looking. I want them all to come home. The new one gives me a better chance.”

Silence. Then the sound of a staffer’s pen learning how to spell the word yes.

Sloan died in March.

Not in a firefight. Not in glory. In his sleep at fifty-four, because hearts don’t get the memo about loyalty. The funeral was small because the best ones are. His wife wore a plain dress and a face brave enough to hold the rest of us together. The ocean did what oceans do—kept talking to shore.

After the flag folded itself into geometry, after the bugle’s last note found the sky and made a deal with it, Torres stood beside me and swallowed hard.

“He kept the napkin,” he said.

“What napkin?” I asked, and then I remembered: LOOK ‘EM IN THE EYES. IF THEY’RE NOT HOME, BRING ‘EM BACK.

“In his wallet,” Torres said. “Like scripture.”

I took a breath that hurt. “Then it is,” I said.

We met at the chow hall that night, a handful of us who knew him before and after the legend. We told stories about the time he chewed out a captain for calling a corpsman “son” because the corpsman outranked him in competence. We laughed in present tense because the past is too cruel a verb to carry alone.

I went home and wrote a new page for the Salute Standard. It was one sentence long: NAME WHAT SAVED YOU. TEACH IT TO SOMEONE ELSE.

Spring pressed its palm to the city’s forehead and declared us fevered but functional. The cherry blossoms failed to apologize for being beautiful while we were all so busy. Frank began attending a group at the VA where they don’t ask you to talk about your war; they ask you how you sleep. He improved by admitting he didn’t. He called me after one session and said, “I told them about the parking lot.”

“What parking lot?” I asked, leafing through a folder I was pretending not to be late with.

“At your wedding,” he said. “How I stood outside. How I left. A Marine named Pittman told me he’d done the same at his daughter’s graduation. He went back the next day and sat on the bleachers by himself until he could stand the sound of other people’s pride.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“I sat in my car,” he said. “And then I went home and took the medals out of the case. Left the glass open.”

“Air,” I said.

He exhaled. “Air,” he agreed.

I kept teaching. It’s what I am when I peel everything else back. The workshop at the academy was full of cadets who knew their futures in broad strokes but not the fine lines. I showed them how to brief like they owed the room an exit ramp for ego. I showed them how to stand without stealing the oxygen. During a break, a young woman with a scar that turned her smile into a thunderbolt approached.

“Ma’am,” she said. “At your wedding—was the ‘Admiral on deck’ planned?”

“No,” I said. “It was chosen.”

She looked at the floor as if permission lived there. “Then you didn’t need your father?”

I considered. “I needed him to be who he was so I could be who I am. Turns out both of us had to change anyway.”

She nodded. “My dad sells tires. He calls me ‘professor’ because I read too much. He thinks the military will ruin that.”

“Let it sharpen it,” I said. “Bring him a book you love and ask him to read a page out loud. When he hears his voice with your words in it, he’ll start to understand.”

She smiled and wrote that down. Later she sent me a photo: her father, grease on his hands, reading out loud under a fluorescent light. It’s the best picture in my office.

The second anniversary came and went like a ship that knows the channel. Frank started showing up to events without standing in the back. He didn’t speak. He didn’t have to. His presence edited the room toward grace. At the end of one panel, a young private asked for a photo with me and then, shyly, with him. Frank froze for half a second, then smiled from a place I don’t remember seeing when I was ten. “Only if you send it to your mother,” he said. “She’ll want to see who you stood next to today.”

The private nodded. “Yes, sir,” he said. “Both of you.”

Afterward, Frank and I walked out into a rain that couldn’t decide. He stuck his face into it like a man introducing himself to weather he had ignored for too long. “I used to think being a father was issuing orders,” he said. “Turns out it’s after-action reports. You write down what you did wrong and you fix what you can before the next deployment.”

“We’re still deployed,” I said.

“To life,” he said, and we both laughed at how true cliches can feel when you finally earn them.

The call came from a reporter who earns his living by being inconvenient at the right time. He had gotten wind of a procurement angle none of us liked—supplements at selection that didn’t belong in bodies we intended to keep past thirty. He wanted comment. I gave it: Not on my watch. Not in my house.

The investigation turned fast. We disciplined a commander who should have known better and a captain who did. We changed a contract structure that made cutting corners a sport. I testified again. This time, nobody asked if I was lowering the standard. They asked what else we were missing.

“Anything you don’t audit because you trust tradition,” I said. “Look there.”

When the scandal ran its course, the same columnist who had tried to humiliate us wrote an editorial that read like an apology written in code. He didn’t say I’m sorry. He said the program had teeth. I don’t need teeth in print. I need them on a deck, in a classroom, on a beach at 0300 where boys become men and men become something that watches over other people’s sons and daughters like a vow. But I cut the piece out and taped it inside a file anyway. Not as a trophy. As a record.

Late summer the year after Sloan died, we held a small ceremony on a pier that had learned more names than most churches. We installed a bench with his name on it and the napkin quote burned into wood no storm could erase. Frank stood beside me, quiet, hands behind his back—not parade rest, exactly, but a cousin of it. James read the words because his voice is the one I want at the end of all my pages.

Afterward, Torres pressed a coin into my palm. “Challenge coin,” he said. It was Sloan’s. On the back, in a hand that had learned patience late, someone had scratched three letters: S.S.M.

“Salute Standard Manual?” I guessed.

Torres shook his head. “Sloan’s Secret Message.”

“What is it?”

He smiled. “He never told me. He said you’d know.”

I turned the coin over and felt the weight of every room I’d ever asked to be quiet. “See someone. Save many,” I said.

Torres nodded. “That’s what I thought,” he said.

We renewed our vows the third year. Not for show. For muscle memory. We stood in the same chapel where the SEALs had stood. Fewer people this time. Enough. Frank sat with James’s parents. He wore a tie that had seen too many funerals and not enough weddings. The chaplain from our first ceremony was deployed. A young lieutenant read the blessing with a voice that remembered choir practice and firefights.

When we turned to face the aisle, a voice came from the back—not shouted, not barked. Just offered.

“Admiral on deck.”

I looked up. It was Frank. His hand was at his side. His eyes were at attention.

The room didn’t stand. They didn’t need to. I did. I stood taller than my four stars. Taller than my childhood. I saluted my father. He returned it. It was imperfect. It was perfect.

Outside, under a sky that decided to be kind, James took my hand. “Satisfied?” he asked, the way he does when he knows I am.

“Deeply,” I said. “Not because anyone lost. Because we all left standing.”

There are days when the work feels like trying to teach the sea to stop picking favorites. Then a letter arrives from a mother whose son didn’t die because we changed a schedule. Or a cadet sends a photo of her father reading in a tire shop. Or a private walks up after a briefing and says, “Ma’am, I was going to quit. I won’t.”

On those days, I take the Emily Dickinson off the shelf and read the storm poem again. I trace my mother’s note with a finger that has learned to hold weapons and hands with the same care. Then I go to work.

Sometimes Frank calls in the evening to tell me what the weather is doing in a town I haven’t visited in years. “We had hail,” he’ll say, like a confession. “It dented the truck. Didn’t touch the flag.”

“Wind is merely a place to learn,” I remind him.

He laughs. “Your mother would have liked you in uniform,” he says.

“She did,” I say. “She always did.”

James will ask if I want tea, and I’ll say water. He’ll press his thumb against the wobbly leg of the table, and it will hold because that’s how tables and promises work if you check them every day.

And sometimes, when I pass a mirror, I’ll catch a white glint at my shoulder and think of the aisle and the echo and the man who texted disgraceful because he didn’t know another word yet. I’ll think of the men who stood without being told. I’ll think of a coin with letters nobody but us needs to translate.

Then I’ll square my cover, open the door, and step into a world that keeps trying to write my story without me. It can try. I’ve got the pen. I’ve got the map. I’ve got a bench on a pier and a program with a name that reminds me why we stand.

“Admiral on deck,” some rooms say when I enter.

“People on deck,” I correct, every time. And we get to work.